There are so many examples of new animal species found through mitochondrial DNA analysis that I believe this should be a routine part of species descriptions. Using morphology alone, taxonomists have often overlooked species that are readily apparent on mitochondrial DNA analysis, including in what should be ideal circumstances using intact adult specimens of large, abundant, and/or economically important organisms. Morphologic characters have been found in some cases but only after DNA has led the way, indicating the discovery process would have been much faster if DNA were analyzed at the beginning. Speed is likely a good way to attract funding, as the public will want the fastest and therefore most economical approach. Mitochondrial DNA analysis can also help extinguish synonomies which have persisted in literature for decades (eg Siddall and Budinoff 2005. Conservation Genetics 6:467).

Under current practice, species recognition whether big or small can be slow (see also earlier post with timeline for discovery of New York Central Park centipede).

Do you see a new species anywhere? Baleen whale specimen collected in 1976, new species description 27 years later based in part on mitochondrial DNA characters (Wada et al. 2003. Nature 426:278)

Do you see a new species anywhere? Baleen whale specimen collected in 1976, new species description 27 years later based in part on mitochondrial DNA characters (Wada et al. 2003. Nature 426:278)

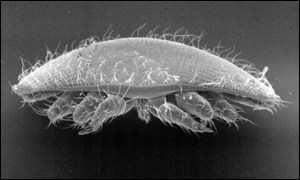

Does this look like 1904? Honeybee mite Varroa jacobsoni described in 1904. In 1970’s, worldwide epidemic infestation of honeybees presumed due to V. jacobsoni began in Asia. 30 years later, epidemic discovered to be due to a new species, V. destructor (Anderson and Trueman 2000. Exp Appl Acarology 24:165). Species description based on mitochondrial DNA divergence; no morphologic characters other than body size.

With funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, researchers at Reveo, Inc. and the University of Washington are collaborating on developing a

With funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, researchers at Reveo, Inc. and the University of Washington are collaborating on developing a

Brower’s article argues about how many Astraptes species are supported by the sequence data, worries about possible consequences of the rise of DNA barcoding, and misses the scientific opportunity to examine this very young species complex with a large set of morphologic, ecologic, and sequence data. He concedes “there are probably at least three species” but declines to put forth what criteria can be used to delimit species. I was surprised to read that the question of whether two sequences “belong to the ‘same species’ is a metaphysical one”.

Brower’s article argues about how many Astraptes species are supported by the sequence data, worries about possible consequences of the rise of DNA barcoding, and misses the scientific opportunity to examine this very young species complex with a large set of morphologic, ecologic, and sequence data. He concedes “there are probably at least three species” but declines to put forth what criteria can be used to delimit species. I was surprised to read that the question of whether two sequences “belong to the ‘same species’ is a metaphysical one”.

A year ago in Science,

A year ago in Science,  a what is thought to be a well-understood group, stomatopods, commonly known as mantis shrimp. Stomatopods are marine crustaceans distinct from true shrimp and are thought to include about 400 species worldwide. Like many marine species, they have a bipartite life cycle where dispersal is achieved through a planktonic larval developmental stage. However, larval stages are notoriously difficult to identify morphologically. Barber and Boyce first established a database of COI DNA barcodes from adult forms of nearly all known species. They then applied DNA barcoding to planktonic larvae collected in light traps at locations in the Pacific Ocean and Red Sea. Comparison of

a what is thought to be a well-understood group, stomatopods, commonly known as mantis shrimp. Stomatopods are marine crustaceans distinct from true shrimp and are thought to include about 400 species worldwide. Like many marine species, they have a bipartite life cycle where dispersal is achieved through a planktonic larval developmental stage. However, larval stages are notoriously difficult to identify morphologically. Barber and Boyce first established a database of COI DNA barcodes from adult forms of nearly all known species. They then applied DNA barcoding to planktonic larvae collected in light traps at locations in the Pacific Ocean and Red Sea. Comparison of  sequences from 189 larval forms revealed 22 distinct larval operational taxonomic units (OTUs), but a minority of these matched known species, suggesting that stomatopod species diversity is underestimated by a minimum of 50% to more than 150%. Their results support general use of DNA barcoding as a rapid, relatively-inexpensive first step in cataloging marine species with planktonic larvae. A similar approach has been applied on land by Smith et al “

sequences from 189 larval forms revealed 22 distinct larval operational taxonomic units (OTUs), but a minority of these matched known species, suggesting that stomatopod species diversity is underestimated by a minimum of 50% to more than 150%. Their results support general use of DNA barcoding as a rapid, relatively-inexpensive first step in cataloging marine species with planktonic larvae. A similar approach has been applied on land by Smith et al “