DNAHouse: exploring the urban environment with DNA

“We identified 95 different animal species.”

You probably wouldn’t believe me if I told you that all of the species displayed above were found in local supermarkets and homes in New York City. A feather from a duster yielded ostrich DNA. A delicacy labeled “sturgeon caviar” instead turned out to be from the strange-looking paddlefish. A popular Asian snack was revealed as giant flying squid. Bison DNA was found in a dog biscuit.

We found DNA evidence all around us. We found DNA “name tags” in all kinds of human and pet foods including raw, cooked, dried, and processed items. We obtained DNA from dried soup mix, scrambled eggs, dog food, chicken McNuggets, hamburger, beef jerky, bologna, yogurt, cheese and even butter. By analyzing DNA, we traced tiny, unrecognizable bits of once-living things to their source.

We could identify animals from what they left behind in the environment. We found tell-tale DNA in dried-out horse manure in Central Park, a pigeon feather on the sidewalk and a shed snakeskin.

DNAHouse attracted news interest

- New York Times: “Through DNA testing, two students learn what’s what in their neighborhood.” December 28, 2009 print web

- New York Post: “Doing Their ‘Pest.’” December 26, 2009 print web

- Washington Post: “At U.S. dinner tables, the food may be a fraud.” March 30, 2010 print web

- BioSciences: “DNA barcoding investigations bring science to life.” January 2010 print web

- NBC evening news December 29, 2009 video

- Channel One video

- WNYC January 15, 2010 podcast

- NPR’s Science Friday: High schoolers give hot dog a DNA test. January 22, 2010. video

DNAHouse investigators

Brenda Tan and Matt Cost, The Trinity School, New York, NY

Advisor: Mark Stoeckle, MD, The Rockefeller University

“We found DNA evidence all around us”

What we did:

We collected 217 specimens from apartments, stores, and outdoors, photographed and labeled them, and delivered our specimens to the American Museum of Natural History for DNA barcode analysis. We matched sequences from our specimens to records in Barcode of Life Database and GenBank.

What we found:

- DNA evidence of 95 species.

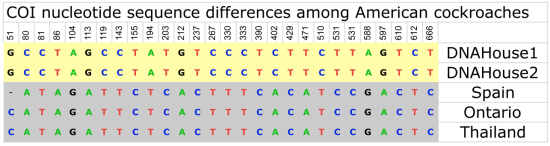

Surprise: A genetically distinct “mystery” cockroach that might be a new species. By appearance it looks like the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) but it is genetically different from other American cockroaches in the databases.

- DNA “name tags” survived in processed foods.

Surprises:- 16% of food items were mislabeled (e.g., “sheep’s milk cheese” made from cow’s milk)

- water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis)(aka “yak”) is the source of buffalo mozzarella

- Canned goods were an exception; only 1/20 yielded DNA, probably due to heat and acid conditions

- DNA in household items, including feather duster (ostrich) and hairbrush (human).

- DNA helped us be expert identifiers, including for items that were unrecognizable.

- a long-legged centipede in an apartment turned out to be a house centipede (Scutigera coleoptrata)

- a tiny spider from an attic was a triangulate cobweb spider (Steatoda triangulosa)

- a squished insect in a box of grapefruit from Texas was the fly Chrysomya megacephala, an invasive species

- DNA was durable indoors and out, helping identify humans and other animals from what they leave behind.

- Human DNA from an old hairbrush

- Pigeon DNA from a feather on the sidewalk

- Horse DNA from dried manure in Central Park

For more information

- Exploring with DNA in New York City: Q and A and narrative report by Brenda Tan and Matt Cost

- Hi-res Image gallery

- Center for Conservation Genetics, American Museum of Natural History

- Press Release

- Specimen details:

About the Bar Code of Life site

This web site is an outgrowth of

the Taxonomy, DNA, and Barcode of Life meeting held at Banbury

Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, September 9-12, 2003.

It is managed by Mark Stoeckle at the Program

for the Human Environment (PHE) at The Rockefeller University.

Contact: mark.stoeckle@rockefeller.edu

About the Program

for the Human Environment

The involvement of the Program for the Human Environment in DNA

barcoding dates to Jesse Ausubel's attendance in February 2002

at a conference in Nova Scotia organized by the Canadian Center

for Marine Biodiversity. At the conference, Paul Hebert

presented for the first time his concept of large-scale DNA

barcoding for species identification. Impressed by the

potential for this technology to address difficult challenges

in the Census of Marine Life, Jesse agreed with Paul on

encouraging a conference to explore the contribution

taxonomy and DNA could make to the Census as well as other large-scale

terrestrial efforts. In his capacity as a Program Director of

the Sloan Foundation, Jesse turned to the Banbury Conference

Center of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, whose leader Jan

Witkowski prepared a strong proposal to explore both the

scientific reliability of barcoding and the processes that

might bring it to broad application. Concurrently, PHE

researcher Mark Stoeckle began to work with the Hebert lab on

analytic studies of barcoding in birds. Our involvement in

barcoding now takes 3 forms: assisting the organizational

development of the Consortium for the Barcode of Life and the

Barcode of Life Initiative; contributing to the scientific

development of the field, especially by studies in birds, and

contributing to public understanding of the science and

technology of barcoding and its applications through improved

visualization techniques and preparation of brochures and other

broadly accessible means, including this website. While the

Sloan Foundation continues to support CBOL through a grant to

the Smithsonian Institution, it does not provide financial

support for barcoding research itself or support to the PHE for

its research in this field.