Human filariasis, caused by various species of insect-transmitted parasitic nematodes, affects more than 120 million persons in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia, and includes elephantiasis and river blindness. In 7 january 2009 Frontiers Zool, 10 researchers from 5 institutions in Italy, France, Japan, and Venezuela apply DNA barcoding and traditional morphologic taxonomy to identification of parasitic filarioid worms. According to the authors, a molecular tool for identification of filiaria is a “desirable goal for many reasons” including “parasites conferred to diagnostic laboratories are often of poor quality due to the difficult[y] of sampling adults and undamaged organisms,” as a “method for the identification of filarioid nematodes in vectors,” and “nematode biodiversity is still highly underestimated both at the morphological and molecular level.”

Human filariasis, caused by various species of insect-transmitted parasitic nematodes, affects more than 120 million persons in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia, and includes elephantiasis and river blindness. In 7 january 2009 Frontiers Zool, 10 researchers from 5 institutions in Italy, France, Japan, and Venezuela apply DNA barcoding and traditional morphologic taxonomy to identification of parasitic filarioid worms. According to the authors, a molecular tool for identification of filiaria is a “desirable goal for many reasons” including “parasites conferred to diagnostic laboratories are often of poor quality due to the difficult[y] of sampling adults and undamaged organisms,” as a “method for the identification of filarioid nematodes in vectors,” and “nematode biodiversity is still highly underestimated both at the morphological and molecular level.”

Ferri and colleagues analyze diagnostic utility of 12S and barcode-region COI sequences and morphologic examination by experts to an assemblage of data from 165 individual specimens (73 newly analyzed for this study) representing about 60 species. Their data set encompasses most of the important human and animal filarioid parasites, including Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi, agents of human tropical elephantiasis, Loa loa (human ocular filariasis), Onchocerca volvulus (human river blindness), and Dirofilaria immitis (dog and cat heartworm), plus specimens recovered from wild animals ranging from bats to toads.

The authors applied a medical test approach to the sequence data, looking at which distance cutoffs produced “minimum cumulative error,” in which they include type I false positive (failure to assign to correct species, analogous to oversplitting) and type II false negative (failure to distinguish between species; analogous to lumping). I find their approach refreshing in that it recognizes the uncertainty inherent in any identification method. Even “gold standard” tests have error rates. Just as a medical laboratory considers a range of factors when adopting a new test method–cost, speed, sensitivity, accuracy, replicability, and training requirements, for example, we might usefully look at methods for species identification, including traditional morphologic techniques, in a similar way. In taking such an approach, we can recognize there are often marked differences between the methods we use to detect something and the methods used to define it.

As a medical testing example, automated systems for rapid detection of bacteria in blood cultures rely on monitoring pressure changes in headspace gas in liquid culture bottles, as growing bacteria consume or produce gases. At the same time we do not define bacteria as “organisms that produce pressure changes in laboratory culture bottles,” for example. Similarly, percent differences between nucleotide sequences of the test specimen and those in a reference library might be a rapid way to “detect” a species, but this does not mean these are a defining characteristic of a species. We recognize species conceptually as independent evolutionary lineages, and practically on the basis of discriminatory characters (eg morphologic, behavioral, or nucleotide substitutions at specific sites). In the day-to-day work of specimen identification and detection of new species however, sequence distances may work just fine as diagnostic signatures.

Back to the article. Ferri and colleagues report COI worked better than 12S as a diagnostic, primarily due to difficulty in finding a consistent algorithm for aligning 12S sequences. With COI, the minimum cumulative error was 0.62% at a K2P distance threshold of 4.8%. The errors were due to low interspecific distances between 2 congeneric pairs [Onchocerca volvulus (human host) and O. ochengi (cattle); Cercopithifilaria longa (Japanese serow, a goat-antelope) and C. bulboidea (Sika deer); might some of the morphologic differences between these species pairs represent phenotypic changes induced by the different hosts?]. More sampling within species will help determine if it is possible to molecularly discriminate among these species using a character- rather than distance-based method.

The authors call for an integrated taxonomic approach to solve discrepancies between morphologic and molecular methods, and conclude “we propose DNA barcoding as a reliable, consistent, and democratic tool for species discrimination in routine identification of parasitic nematodes.”

Just as new telescopes reveal previously hidden details of the universe, genetic surveys regularly reveal previously hidden (aka cryptic) species. Of course these species are cryptic only in the sense that morphological analysis is not the right tool to “see” them with. To my ear the word “cryptic” suggests camouflaged organisms that blend in with the environment, such as the Dead leaf butterfly Kallima inachus. Unlike camouflage, which is presumably a protection adaption, it is my impression there is nothing biologically special about morphologic crypsis except for the difficulty we have in recognizing it; that is, what we call cryptic species exhibit the same sorts of distinct ecological and behavioral adaptations found in those whose differences are more visible to the human eye.

Just as new telescopes reveal previously hidden details of the universe, genetic surveys regularly reveal previously hidden (aka cryptic) species. Of course these species are cryptic only in the sense that morphological analysis is not the right tool to “see” them with. To my ear the word “cryptic” suggests camouflaged organisms that blend in with the environment, such as the Dead leaf butterfly Kallima inachus. Unlike camouflage, which is presumably a protection adaption, it is my impression there is nothing biologically special about morphologic crypsis except for the difficulty we have in recognizing it; that is, what we call cryptic species exhibit the same sorts of distinct ecological and behavioral adaptations found in those whose differences are more visible to the human eye. Gustafsson and colleagues were initially studying a neuropeptide gene FMRFamide using L. variegatus purchased from a commercial supplier in California, with puzzling results suggesting polyploidy with multiple gene copies. This lead them to further characterize approximately 50 individuals collected at multiple sites in Europe and North America. Sequencing of COI, 16S, and ITS sorted the specimens into 2 phylogenetically distinct (maximum parsimony and Bayesian analysis) clades with 17% mean difference in COI, with the same genetic structure in mitochondrial COI/16S as nuclear ITS. Both clades were found in North America and Europe, sometimes at the same site. The authors conclude “it thus seems reasonable to regard these two main lineages within the L. variegatus complex as different species, regardless of which species concept one adheres to.” Of course, it may be they have rediscovered a named species; they caution that more study needs to be done including sampling the other named species in genus Lumbriculus (

Gustafsson and colleagues were initially studying a neuropeptide gene FMRFamide using L. variegatus purchased from a commercial supplier in California, with puzzling results suggesting polyploidy with multiple gene copies. This lead them to further characterize approximately 50 individuals collected at multiple sites in Europe and North America. Sequencing of COI, 16S, and ITS sorted the specimens into 2 phylogenetically distinct (maximum parsimony and Bayesian analysis) clades with 17% mean difference in COI, with the same genetic structure in mitochondrial COI/16S as nuclear ITS. Both clades were found in North America and Europe, sometimes at the same site. The authors conclude “it thus seems reasonable to regard these two main lineages within the L. variegatus complex as different species, regardless of which species concept one adheres to.” Of course, it may be they have rediscovered a named species; they caution that more study needs to be done including sampling the other named species in genus Lumbriculus (

In

In

In another seeming step towards Jurassic Park, two groups of researchers recovered full-length mitochondrial DNA sequences from 22,000 to 44,000 year-old bones of extinct European and North American bears. Full-length mtDNA has been recovered from similarly ancient specimens, but in those cases frozen tissues preserved in permafrost were used. Both groups used specialized PCR protocols employing several hundred primer pairs designed to recover short fragments, rather than one of the newer sequencing technologies, demonstrating the continued power of DNA amplification.

In another seeming step towards Jurassic Park, two groups of researchers recovered full-length mitochondrial DNA sequences from 22,000 to 44,000 year-old bones of extinct European and North American bears. Full-length mtDNA has been recovered from similarly ancient specimens, but in those cases frozen tissues preserved in permafrost were used. Both groups used specialized PCR protocols employing several hundred primer pairs designed to recover short fragments, rather than one of the newer sequencing technologies, demonstrating the continued power of DNA amplification. sister to Tremarctos ornatus (Spectacled bear). Of course it would be difficult to recover a full-length sequence–what about the

sister to Tremarctos ornatus (Spectacled bear). Of course it would be difficult to recover a full-length sequence–what about the  Trewick focused on Sigaus australis species complex, which includes the apparently widely-distributed S. australis, and 5 sympatric or parapatric species with much narrower ranges (S. childi, S. obelisci, S. homerensis, and 2 undescribed species). Within this complex he analyzed 160 individuals collected at 26 locations (mostly S. australis (136 individuals) and 1-13 individuals for the more restricted species). For mtDNA analysis, an approximately 600 bp region of 12-16S and about 500 bp of 3′ COI (ie not overlapping COI barcode region!) were examined.

Trewick focused on Sigaus australis species complex, which includes the apparently widely-distributed S. australis, and 5 sympatric or parapatric species with much narrower ranges (S. childi, S. obelisci, S. homerensis, and 2 undescribed species). Within this complex he analyzed 160 individuals collected at 26 locations (mostly S. australis (136 individuals) and 1-13 individuals for the more restricted species). For mtDNA analysis, an approximately 600 bp region of 12-16S and about 500 bp of 3′ COI (ie not overlapping COI barcode region!) were examined. Regarding point 2, genetic methods including DNA barcoding may not resolve very young species. For Sigaus sp. grasshoppers, nuclear sequence data will help sort out whether these are young species or the products of recent hybridization or introgression.

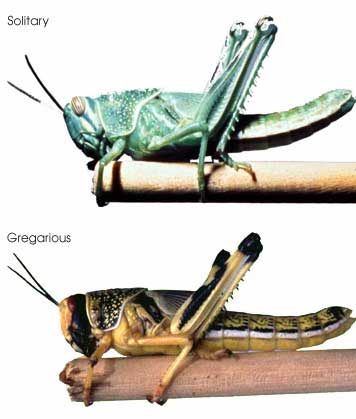

Regarding point 2, genetic methods including DNA barcoding may not resolve very young species. For Sigaus sp. grasshoppers, nuclear sequence data will help sort out whether these are young species or the products of recent hybridization or introgression.  In this regard, I am struck by the apparent variability in some grasshopper species, as in the color morphs of S. childi shown above. It brings to my mind the extraordinary transformations from solitary grasshoppers to swarming locusts (these are members of the same Acrididae family as Sigaus). Perhaps grasshopper genetics include analogous latent “switches” that might enable relatively rapid evolutionary transformations.

In this regard, I am struck by the apparent variability in some grasshopper species, as in the color morphs of S. childi shown above. It brings to my mind the extraordinary transformations from solitary grasshoppers to swarming locusts (these are members of the same Acrididae family as Sigaus). Perhaps grasshopper genetics include analogous latent “switches” that might enable relatively rapid evolutionary transformations. The DNA barcode initiative aims to establish a universal identification system for plant and animal species by analyzing a standardized genetic locus (or for plants, a small set of loci). In addition to making analysis cheaper, standardizing on one or a few loci enables a diverse assemblage of researchers to work together to build an interoperative library.

The DNA barcode initiative aims to establish a universal identification system for plant and animal species by analyzing a standardized genetic locus (or for plants, a small set of loci). In addition to making analysis cheaper, standardizing on one or a few loci enables a diverse assemblage of researchers to work together to build an interoperative library.