Following the first Banbury workshop in March 2003, Jesse Ausubel and I wrote a “Draft Scientific Rationale and Strategy” that described DNA barcoding as ““Google” for Life Forms” (with the name in quotes in case readers didn’t get the reference, hard to imagine today!). One year and a second Banbury workshop later the Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL) was inaugurated at Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC.

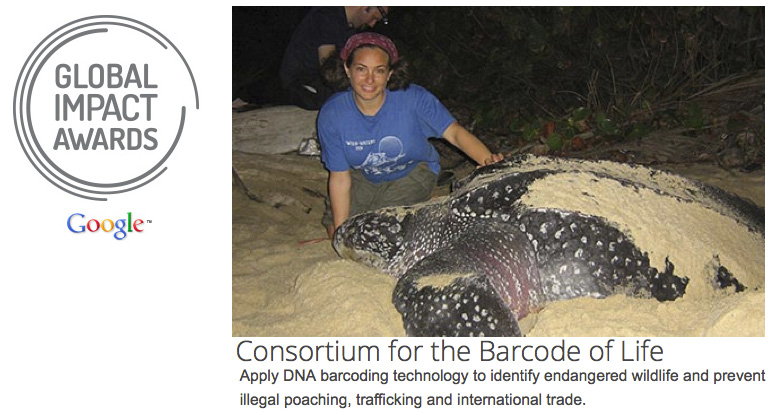

This week the Google Foundation announced a $3 million Global Impact Award to CBOL to enable a DNA barcode reference library for endangered species (and their close relatives) as a tool to prevent illegal wildlife trafficking. As in 2003, this is a wonderfully natural pairing of organizations and a cause for the entire barcoding community to celebrate.

In the language of today, we can see the DNA Barcoding/Google for Life Forms is a kind of “open access” to taxonomic knowledge. It may turn out that the ability to identify species, like the ability to search the internet, will have wider consequences than we currently forsee. In The Viral Storm: The Dawn of a New Pandemic Age (2011), author Nathan Wolfe cites the 2008 high school student DNA barcoding ‘Sushi-gate’ project as “one of the first notable examples of nonscientists “reading” genetic information.” As a Cassandra, Wolfe envisions this as a first step towards DIY bioterrorists but I imagine it is more likely a first step towards DIY biologists sequencing everything in sight, helping monitor the health of the environment, including tracking spread of human and animal diseases.