Area of Research: Energy and Climate

Climatic constraints and human activities: Introduction and overview

Self-sinking capsules to investigate Earth’s interior and dispose of radioactive waste

CO2: an introduction and possible board games

Technical Progress and Climatic Change

1. Introduction

One hundred years ago icebergs were a major climatic threat impeding travel between North America and Europe. 1,513 lives ended when the British liner Titanic collided with one on 14 April 1912. 50 years later jets overflew liners. Anticipating the solution to the iceberg danger required understanding not only the rates and paths on which icebergs travel but the ways humans travel, too.

My premise is that nearly everyone in the global warming debate, from atmospheric scientists and agronomists to energy engineers and politicians, largely neglects to consider, and thus underestimates, the importance of technical change in considering reduction in greenhouse gases and adaptation to climate change.

Of course, not all technical change is good, with respect to climate or any other facet of our world. Technology can destroy as well as better us. Advances in technology such as the internal combustion engine have generated the outpouring of greenhouse gases in the first place. When Alfred J. Lotka made his landmark projection of anthropogenic climatic change in 1924, he figured 500 years to double atmospheric carbon. He did not foresee the explosion of energy demand and the gadgets that collectively would make the mushroom possible.

Technical change, the blind spot in Lotka’s otherwise remarkably perceptive work, is precisely my focus. To think reliably for the long-term, we must question carefully what stays the same and what can change.

For purposes of this paper, let us assume that most innovation is humane and responsible. A companion exercise which emphasizes demonic aspects of technology and technological failures in the face of climate change would certainly also be worthwhile.

Not all human societies need have asked our question about technical progress in the face of climatic change. For some societies, time stands still or cycles with little development. Of course, the function of innovation has existed in all civilizations. Medieval European guilds, for example, transmitted knowledge about their crafts along dozens of generations, combining it with many inventions. Many inventions originated in China, of which gunpowder and the spinning wheel are among the most famous.

But something new happened in Western civilization about 300 years ago. One might call it organized social learning. Successful societies are learning systems, as Cesare Marchetti observed (1980). In fact, the greatest contribution of the West during the last few centuries has been the zeal with which it has systematized the learning process. The main mechanisms include the invention and fostering of modern science, institutions for the retention and transmission of knowledge (such as universities), and the aggressive diffusion of research and development throughout the economic system.

Attempts have been made to quantify the takeoff of modern science and technology. Early in the 20th century the German chemist Ludwig Darmstaedter carefully listed important scientific and technological discoveries and inventions back to 1400 AD. The list is certainly not complete, but it may be representative. The message is firm: some kind of take-off, albeit bumpy, did occur about 1700, and by 1900 the level of activity was an order of magnitude higher (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Decadal number of scientific and technological discoveries, 1400- 1900. Source of data: L. Darmstaedter, 1908.

Fear that humanity was running out of inventions partly motivated Darmstaedter’s history. Scientists and engineers themselves have often stated that the pool of ideas is near exhaustion. In 1899 Charles H. Duell, U.S. Commissioner of Patents, urged President William McKinley to abolish the Patent Office, stating “Everything that can be invented has been invented” (Cerf and Navasky, 1984, p. 203). After the telephone and electric light what could follow? Darmstaedter’s lists peaked about 1880.

In fact, we do know that invention and innovation are not distributed evenly but come in spurts (Mensch, 1979). But they have come with ever increasing intensity. The slow periods for diffusion of innovations flatten the world economy and drain confidence from many of us. Perhaps the 1990s are an economic trough. In any case, understanding the accumulated surges of technical progress during the 20th century can help us glimpse 2050 and 2100, when the heat may be on.

2. Evidence of Technical Progress

Let us begin with examples from computing, communications, and transport.

Modern computing began in the late 1940s with the ENIAC machine, operating on vacuum tubes. One of the first customers for the most advanced machines was always the U.S. military, in particular, the national laboratories such as Los Alamos, which designed nuclear weapons. The top computer speed at Los Alamos, shown in Figure 2, increased one billion times in 43 years.

Figure 2. Computer speed, Los Alamos National Laboratory. Source of data: Worlton: 1988.

We know that mechanical and electromechanical calculating machines had a history of improvement before John von Neumann and others began to tinker in the 1940s. And we know that the current Cray machines are not the ne plus ultra. Parallel machines already promise a further pulse of speed. Quantum computing looms beyond (Lloyd, 1993).

When Darmstaedter wanted to telephone, he was no doubt excited by the speed and distance his message could travel but probably frustrated by the capacity of the available lines. Long-distance calls had to be booked in advance. In the days of the telegraph it was one line, one message. In one hundred years, as Figure 3 shows, engineers have upped relative channel capacity by one hundred million times. In fact, fiber optics appear to initiate a new trajectory, above the line that described best performance from 1890 to 1980.

Figure 3. Communication channel capacity. Source: Patel, 1987.

Without computers, modern numerical climate models would not be tractable. Without telecommunications, global conferences would be difficult to organize. Without airplanes, Americans would rarely attend meetings in Europe. In 1893 it probably would have required three weeks to travel from a laboratory in Stanford, California, to a conference hall in Laxenburg, Austria, assuming no detours from icebergs. Airplanes first shrank our continents and then made it possible to hop from one to another.

Propulsion for aircraft, shown in Figure 4, has improved by one hundred thousand in 90 years. In fact, we can see clearly that the aeronauts have exploited two trajectories, one for pistons, ending about 1940, and one for jets, culminating in the present.

Figure 4. Performance of aircraft engines. After Gruebler, 1990. Sources of data: Angelucci and Matricardi, 1977, Grey, 1969, Taylor, 1984.

The aircraft engines exemplify that continuing improvement of any technology eventually becomes limited by some physical principle. A new technology then overtakes the old by becoming more cost effective and permitting a broader range of operating characteristics such as speed or bandwidth. The present wave of jet development may have broken. But, linear motors are just starting. These may power the magnetically levitated trains (terra-planes) of the 21st century at 2000-3000 km/hour.

These examples from information, communications, and transport bear importantly on the economy and society as a whole. Yet, one can argue that they matter only indirectly for emissions of greenhouse gases and for adaptation to climatic change. In fact, this view is wrong. Simply recall that weather forecasts, a pre-eminent form of adaptation, are the product of satellites, computers, radio, and video (and earlier, telegraphs and telephones). Assessing prospects for climate change requires broad consideration of technical progress. Nevertheless, let us look at agriculture and energy, where the links between climate and technology are most obvious.

It is common to believe that the revolution in agricultural productivity preceded the revolution in industrial productivity. In the United States, this was not the case. Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia fields yielded roughly the same number of bushels of wheat in 1800 as the average American field yielded until about 1940. Americans harvested more by bringing in more land.

Productivity per hectare took off in the United States in the 1940s, just like jet engines and computers, as is evident from Figure 5. U.S. wheat yields have tripled since 1940, and corn yields have quintupled. Other crops show similar trajectories. Yields in agriculture synthesize a cluster of innovations, including tractors, seeds, chemicals, and irrigation, joined through timely information flows and better organized markets.

Figure 5. Yields of wheat and corn per hectare in the United States, 1880- 1990. After Waggoner, 1994.

Fears are chronic that societies have exhausted their agricultural potential. The Latin church father Tertullian wrote circa 200 AD “The most convincing examinations of the phenomenon of overpopulation hold that we humans have by this time become a weight on the Earth, that the fruits of nature are hardly sufficient for our needs, and that a general scarcity of provisions exists which carries with it dissatisfaction and protests, given that the Earth is no more able to guarantee the sustenance of all. We thus ought not to be astonished that plagues and famines, wars and earthquakes come to be considered as remedies, with the task, held necessary, of reordering and limiting the excess population.”

Two millennia later the agricultural frontier is still spacious, even without invoking genetic engineering of plants. Figure 6, which contrasts annual corn yields for the best growers in Iowa, the average Iowa grower, and the world average, says the world grows only about 20 percent of the top Iowa farmer. Interestingly, the production ratio of the performers has not changed much since 1960. Even in Iowa, the average performer lags more than 30 years behind the state-of-the-art. While technology may progress, rates of diffusion appear to remain stable. And conservative.

Figure 6. Corn yields, Iowa and world, 1960-1991. “Iowa Master” refers to the winner of the annual Iowa Master Corn Growers Contest. Source: Waggoner, 1994.

Though societies are cautious in adopting new practices, recall that the doubling of the pre-industrial level of CO often cited as hazardous is probably 75 or more years in the future. If we had performed a study prior to 1940 of the impacts of CO doubling and climate change on U.S. wheat and corn, the most easily defended assumption would have been constant yields per hectare as a baseline. Neglecting technical progress, the assumption would have brought misleading results. Modern science can now penetrate to every field, cell, and sector of society. It must be taken into account in assessing costs and benefits of strategies for mitigation and adaptation.

One of the technical quests that began about 1700 was to build efficient steam engines. As shown in Figure 7, engineers have taken about 300 years to increase the efficiency of the generators to about 50 percent. Alternately, we are about mid-way in a 600-year struggle for perfectly efficient generating machines. What is clear is that the struggle for energy efficiency is not something new to the 1980s, just the widespread recognition of it.

Figure 7 also explains why we have been changing many light bulbs recently. We have been zooming up a one-hundred year trajectory to increase the efficiency of lamps. The struggle with the generators is measured in centuries. The lamps glow better each decade. The current pulse will surely not exhaust our ideas for illumination. The next century could well reveal new ways to see in the dark, just as quantum computing, linear motors, and bioengineering will reshape our calculations, travel, and food.

Figure 7. Efficiency of energy technologies. Sources: Starr and Rudman, 1973; Marchetti, 1979.

The “cost” of reducing greenhouse gas emissions cannot be properly estimated without understanding the directions in which technical change will drive the energy sector anyway, with regard to preferred primary fuels as well as efficiency. What appear as costs in our current cost-benefit calculus for mitigating, and adapting to, the greenhouse effect may largely be adjustments that will necessarily occur in any case.

This possibility is illustrated by the final technological trajectory discussed here, that of decarbonization, or the decreasing carbon intensity of primary energy, measured in tons of carbon created per kilowatt year of electricity (or its equivalent) (Figure 8). As is evident, the global energy system has been steadily economizing on carbon. Without gloomy climate forecasts or dirty taxes.

Figure 8. Carbon intensity of primary energy, 1900-1990, with projections to 2100. The projection stopping the historic trend of decarbonization is the IPCC 1990 “Business as Usual” (BAU) scenario; IPCC IS92a and ISP2c are high and low energy scenarios from the 1992 Supplement. Sources: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1990, 1992; Ausubel et al., 1988.

In a peculiar choice of words, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1990 designated as “Business-as-Usual” its scenario which stifled and even reversed the 130-year trend. “Business as Usual” was a scenario of technical regression. It essentially ignored the scientific and technical achievement of the past 300 years, including the achievements that make identification and estimation of the greenhouse effect possible. Mr. Duell would have been quite at home with the 1990 IPCC.

For contrast, consider the “methane economy” scenario which essentially squeezes carbon out of the energy system by 2100 (Ausubel et al., 1988). It is perfectly consistent with the technical history and evolution of the energy system. In its 1992 scenarios the IPCC reluctantly began to reflect that society is a learning system and that we are learning to leave carbon.

3. Conclusions

The essential fact is that technological trajectories exist. Technical progress in many fields is quantifiable. Moreover, rates of growth or change tend to be self-consistent over long periods of time. These periods of time are often of the same duration as the time horizon of climatic change potentially induced by additions of greenhouse gases. Thus, we may be able to predict quite usefully certain technical features of the world of 2050 or 2070 or even 2100.

The hard part may be believing that in a few generations our major socio-technical systems will perform a thousand or a million or a billion times better than today.

If we accept that we are not at the end of the history of technology, surely our cost structure for mitigation and adaptation changes. In some cases it may be possible to summarize improving performance in a simple coefficient, such as that used for “autonomous energy efficiency improvement” (Nordhaus, 1992). The need is to have a long and complete enough historic record from which to establish the trend. Most prognosticators live life on the tangent, projecting on the basis of the last 15 minutes of system behavior. Our methods must advance to encompass long time frames.

A complicating factor is that technologies form clusters to reinforce one another and create whole new capabilities. Imagining how the clusters will affect lifestyles and restructure the economy, and thus affect emissions and vulnerability to climate, is a tremendous intellectual challenge. Lotka saw cars and compressors, but he probably could not envision vast air- conditioned cities and suburbs growing in Arizona, Texas, and Florida.

We also do not understand well the malleability of the time constants or rates of technical change. The technical clock ticks. The West did something a few centuries ago to set the whole machine in motion. Over the last 100 years the United States and other countries have gone much further in establishing systems for research and development. The global research and development enterprise is now about $200 billion annually. Will higher investments speed up the clock? Or, are they required just to maintain current rates of progress, with each increment coming at greater cost? The question is open.

Some object to the trajectories of technology because they limit freedom. In fact, they point out promising channels for society to explore. Discovery and innovation can be costly games. Scientists and engineers should be grateful for signs pointing in the right directions and make mitigation and adaptation for climate change cheap.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Perrin Meyer for assistance.

References

Angelucci E, and Matricardi, P., 1977, Practical Guide to World Airplanes, Vols. 1-4, Mondadori, Milan (in Italian), Italy.

Ausubel, J.H., Gruebler, A., and Nakicenovic, N., 1988, Carbon dioxide emissions in a methane economy, Climatic Change 12:245-263.

Cerf, C., and Navasky, V., 1984, The Experts Speak: The Definitive Compendium of Authoritative Misinformation, Pantheon, New York, USA.

Darmstaedter, L., 1908, Handbuch zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Technik, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

Grey, C.G., ed., 1969, Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft, reprint of 1919 Edition, David & Charles, London, UK.

Gruebler, A., 1990, The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures, Physica, Heidelberg, Germany.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1990, Climate Change: The IPCC Scientific Assessment, Cambridge U. Press, England.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1992, Climate Change 1992: The Supplementary Report to the IPCC Scientific Assessment, Cambridge U. Press, England.

Lloyd, S., 1993, A potentially realizable quantum computer, Science 261:1569- 1571.

Lotka, A.J., 1924, Elements of Physical Biology, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore MD, reprinted 1956, Dover, New York, USA.

Marchetti, C., 1979, Energy systems: The broader context, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 15:79-86.

Marchetti, C., 1980, Society as a learning system, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 18:267-282.

Mensch, G., 1979, Stalemate in Technology, Ballinger, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Nordhaus, W.D., 1992, An optimal transition path for controlling greenhouse gases, Science 258:1315-1319.

Patel, C.K.N., 1987, Lasers in communications and information processing, in Ausubel, J.H. and Langford, W.D., eds., Lasers: Invention to Application, National Academy, Washington DC., USA, pp. 45-100.

Starr, C. and Rudman, R., 1973, Parameters of technological growth, Science 182:358-364.

Taylor, J.W.R., ed., 1984, Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1984-1985, Jane’s, London, England.

Tertullian, Apology, Loeb Classical Library 250, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Waggoner, P.E., 1994, How much land can ten billion people spare for Nature? Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, IA, USA.

Worlton, J., 1988, Some patterns of technological change in high performance computers, CH2617-9, Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, New York, USA.

Density: Key to Fake and True News About Energy and Environment

The future environment for the energy business

Does Climate Still Matter?

We may be discovering climate as it becomes less important to well-being. A range of technologies appears to have lessened the vulnerability of human societies to climate variation.

Amidst widespread agreement that the planet is committed to at least some climatic change induced by human activity, there is growing pressure to “slow the greenhouse express” (ref. 1). Here I examine climate through the lens of technology and innovation, to clarify what adaptations have succeeded and the trends in vulnerability to climate. I also examine whether the greenhouse effect by itself will call into play new technologies, or whether the evolution of technology will largely be ‘business as usual’ regardless of climate change. Finally, I identify some ways that government may assist adaptation.

My focus is on adaptability of human systems, including agriculture. Adaptability of ecosystems and the ethics of human behaviour that brings about large scale transformations of the Earth must also be considered in balancing responses to the greenhouse issue.

What are often labeled adaptive measures are themselves the impacts of climatic change. Innumerable adaptations in food, clothing and shelter are responses to the spatial and temporal variability of climate. Humans do not wait guilelessly to receive an impact, bear the loss, then respond with an adaptation. Rather they attempt to anticipate and forstall problems.

Innovations

Technical innovations relevant to climate and their diffusion occur in all societies and sectors and in many forms. Technology includes both hardware (for example, materials, physical structures, devices and machines) and software (rules and recipes for behaviour).

Illustrative innovations of hardware are cisterns and dams to store water, tractors to speed rapid harvests, and new crop cultivars to reduce susceptibility to drought. Perhaps less obvious, but of great importance for adaptation to climate, are information technologies. In the United States, during several years in the 1980s sales of information technologies to the agricultural sector were comparable to sales of farm equipment. The long history of software innovations includes tide tables, irrigation scheduling, and weather forecasts. Along with the readily classified hardware and software are climate related behavioural, social and institutional innovations, such as agricultural credit banks, national parks, green political parties and flood insurance.

Software and social innovations are al most always indispensable for the technology of new hardware. Major innovations, in transportation for example, are in fact clusters of innovations involving not only new materials and physical processes but also new forms of social organization, including financing and management. Transportation systems exemplify technology that has been important in adaptation to climate through expanding the availability of food from a local to a global scale. Reliance on food from afar not only diversifies diet, but also spreads production risks across more climatic zones.

Early communities drew the bulk of their food from small areas. One of the earliest city states, Uruk in Mesopotamia, probably grew most of its sustenance except for animals within 20 kilometres of the city walls2. Two millennia later, Greece and Rome obtained most of their food from overseas colonies across the Aegean and Mediterranean seas3. At its height, Rome acquired 200,000 tons of grain annually for its one million inhabitants, most of it shipped from Africa, Sardinia and Sicily. What marine transportation did in the classical world, the steam locomotive did in the nineteenth century, halving the cost of land transport. The railroads penetrated the great land masses of North America and Australasia. Their operations were little affected by climate, topography or other local conditions. Great parts of the new worlds were dedicated to cultivation of single crops to supply world markets and to smooth availability through the year.

Technological inventions and innovations that have had roles in human ability to adapt to climate over the last 100 years or so range widely4: food preservatives (1873) to over come problems of seasonal food production; light bulbs (1879) to make work safe and effective indoors; aluminum (1887) and other structural materials to resist environmental deterioration; refrigeration (1895) and air conditioning (1902, 1906) to facilitate activity in hot seasons and locations; automobiles (1890s) to provide personal transportation that is much less sensitive to climate than horses or pedal bicycles; mechanical wind shield wipers (1916) to see in the rain; anti freeze (ethylene glycol) (1929) to safeguard motors in winter; frozen food (first sales, 1930) to diversify diet among regions and seasons; radio-beam navigation (1934) to fly in poor visibility; and weather (1960) and Earth resources (1972) satellites for analysis and forecasts of weather and climate.

In many respects we seem to be ‘climate proofing’ society, making ourselves less subject to natural phenomena. For centuries and millennia we relied mainly on behavioural and social adaptation. We took siestas when the sun was high and sought refuge in hill stations in the monsoon season. Large pastoral and nomadic populations followed the seasonal availability of resources and avoided climatic stresses. Much of the planet remained seasonally or entirely uninhabitable for climatic reasons. With current technology many people can live in virtually any climate that now exists. Modern water supply and heating and ventilation systems, along with medicines (for example, quinine and vaccines) and public health measures, have enabled large populations to inhabit formerly uninhabitable regions. By 1980 the population in semiarid, desert and mountain regions had passed 35 million or 15 per cent of the US population5. Lacking modern technology, these zones accomodated less than one per cent of the population in 1860 and six per cent in 1920.

Preferences

The ability to colonize almost the entire planet is due to the human ability to carry with us that particular range of environment in which we can survive and prosper6. In wealthier societies, preferences are shifting toward hot and dry climates that were forbid ding a century ago. Evidence of lessening human vulnerability is also found in health. For example, a flattening of monthly rates of total mortality in Japan between 1899 and 1973 is explained partly by diminution of the previous, climatically driven seasonal peaks7.

Production can now proceed more or less continuously in severe environments. For example, North Sea offshore oil platforms operate 24 hours per day, 365 days per year. At a price, services, such as aviation, are now available at almost all times and places. Aviation began as a system that was extremely sensitive to weather and is increasingly less so, due to expanded range; avionics, radar and guidance systems; understanding of thunderstorms, wind shear, and other weather phenomena; and changes in construction materials. Crops and livestock can now be produced ‘indoors’ protected from the elements. In some cases, alternatives to outdoor production are so advantageous that a crop is displaced. Originally spurred by the need for supplies in wartime, synthetic rubber from petrochemical feedstocks, which is not subject to the vagaries of pests, droughts and floods, and other risks out doors, has overwhelmed natural rubber from trees. In 1990, ten per cent of US fish production was in the controlled environment of fish farms8, up from one per cent in 1980 and projected to reach 20 per cent in 2000.

Consumption is also insulating itself from environment. Inside most shopping malls, for example, only fashions or decorations signal the season. Sports are increasingly played in domed stadiums isolated from the weather. In affluent societies, winter vacations in warm climates have become a popular adaptation to escape climatic impacts.

Forecasting is itself a key technology that reduces vulnerability to weather and hence climate. Forecasts can help accommodate peak loads in electric power systems during heat waves. Improved forecasting, in conjunction with increased incomes and better transportation, has also enabled more people to enjoy recreation in all seasons.

Synchronicity

The decline of ‘synchronicity’, the naturally enforced time regimen of social groups, is a feature of life in advanced societies. In agricultural societies, the rhythm of life is strongly determined and coordinated for al most all by the seasons and the associated demands for labour in the field. In advanced economies, where both production and consumption may proceed almost continuously and only about five per cent of the population farms, weather and climate no longer control schedules. The fact that the peak season for holidays in advanced societies is the late summer, a peak season for labour in agricultural societies, indicates the transformation that has taken place.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s a group of US researchers explored the ‘lessening’ hypothesis of climate impacts9, which states that persistent and adaptive societies, through their technological and social organization, lessen the impacts of recurrent climatic fluctuations of similar magnitude upon the directly susceptible population and indirectly lessen the impacts on the entire society. In the cases studied, substantial evidence was found to support the hypothesis of lessening impacts. For example, in the US Great Plains, the most severe disruptions to livelihood and health occurred during the earliest periods, when incidences of malnutrition and starvation were recorded. Investigation of the more recent periods showed much smaller impacts for comparable drought stress, because of a variety of adjustments and strategies, including more extensive and effective anticipatory action.

An alternative to the lessening hypothesis is that increasingly elaborate technical and social systems insulate us from the adverse effects of recurrent climatic fluctuation at the cost of increased vulnerability to catastrophe from less frequent natural and social perturbations. In a global economy, such vulnerability might be devolved or shared ever more widely. Presumably this vulnerability to catastrophe, surprise or nonlinear effects is what worries many about the greenhouse effect. But the evidence seems to weigh against the suggestion that technology, lifestyles and other forces are creating a more ‘brittle’ system in the face of climate change.

Society appears to proceed along ‘technological trajectories’ that enable, for example, more travel, more financial transactions, and more messages. The succession of technologies that make possible this increased activity appears to diminish in sensitivity to climate. Although it was usually true that neither rain nor sleet stayed the American postman from his rounds, no system of postmen could be as faithful as the modern telecommunications system that now carries a much larger share of messages than the old system of letters. Similarly, a system of energy from wood and hay was more climatically sensitive than one reliant on oil and natural gas. Water and wind power are, of course, more sensitive to climate. In the late eleventh century, the areas under Norman rule in England had about one water mill for every 50 households10, providing power to grind grains, work metal, weave textiles and cut wood. In 1694 France had 80,000 flour mills, 15,000 industrial mills, and 500 iron and metallurgical works, altogether almost 100,000 facilities powered by wind and water. Although such an industrial infra structure is tightly adapted using climatic resources, it is also vulnerable to climate variability and change.

The trend toward less climatic vulnerability also exists in transportation. Well into the nineteenth century, sailing vessels were the preferred long-distance transport and frequently becalmed. World steamship tonnage exceeded sailing tonnage only in 1893. Although coal cost more than wind, steam ships rapidly became cheaper as well as faster than sailing ships, because their schedules were more regular and avoided the circuitous routes required by sailing vessels. Transport underground through tunnels by high-speed magnetically levitated trains is already on the drawing boards in Japan; such systems would be less sensitive to climate than the surface and air systems now in use.

Climate is only one of several factors that have driven the evolution of systems of communications, transport and energy. It is probably secondary. But vulnerability to climate and other environmental forces may be a good proxy for quality and reliability of service. To the extent that the systems evolve in the direction of higher quality and reliability, these trajectories of development may also decrease vulnerability of major systems to climatic change. It would be useful to identify exceptions to this pattern, should they exist.

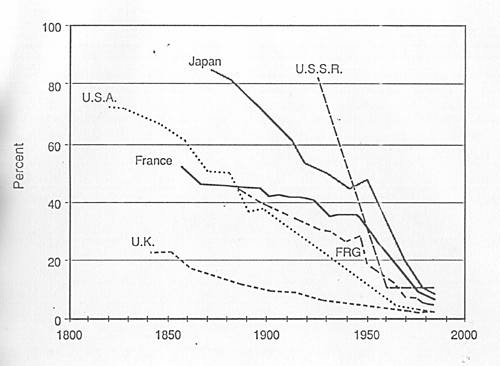

As incomes depend less on activities out of doors, societies become less vulnerable to climate. The trend in all developed countries since the industrial revolution began is away from employment outdoors (Fig. 1) and to ward employment in the service sector, most of which is in climate-controlled office buildings and shops. With a lag of 50-100 years the same trend is found in less developed countries, where 4050 per cent of the population is now engaged in agriculture. if the current trend continues, this fraction should diminish to 20-25 per cent by 2050.

What are the times characteristic of technical innovation and diffusion of technologies in relation to the time of human induced climatic change? Taking account of both C02 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases, major climatic shifts are expected during 40-50 years (ref. 11). A retrospect on technology during the past century suggests the extent of change during the decades to come: in 1890 there was little farming in California and Australia, and key technologies did not yet exist or were not widely applied to impound and transport water, or to transport and store agricultural products promptly; in 1903 the Wright Brothers flew 59 seconds at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, whereas in 1990 in the United States, over 500 million air passengers flew around 450 x 109 miles12; commercial transatlantic aviation, relying on the jet engine, superseded travel by ocean liners about 1960; tourism has been extended to Antarctica, and scientific bases there are occupied year round, despite the fact that it was only in 1911-1912 that Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole and Robert Scott died there; penicillin, the first important antibiotic, was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, and large-scale production began only as recently as 1943; nuclear power for electricity generation first came into use in the late 1950s, but within about 30 years it was able to provide over 70 per cent of France’s electric power; until 1965 no satellites were used for any routine application, whereas satellite systems now girdle the Earth, watching for storms, relaying communications, and helping ships and planes navigate anywhere on the globe; and finally, although the microprocessor was only introduced in 1971 and the personal computer appeared about 1977, Americans are now using over 50 million personal computers.

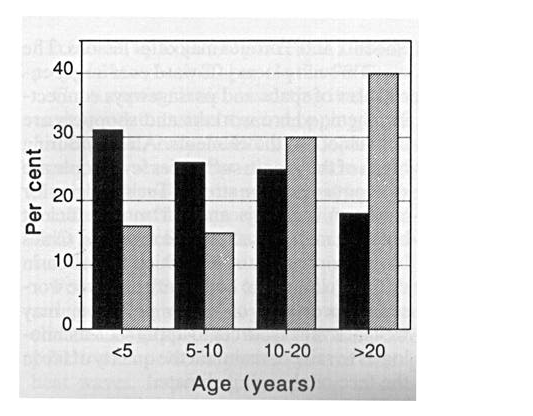

During the period in question and with or without climatic change, technology will transform the way people live. Food, energy, transportation and all the other systems that support human life and the economy will be changed by technologies that can be glimpsed now, such as genetic engineering, fusion, superconductivity and desalination, as well as by technologies yet to be easily pictured. Fifty to a hundred years will allow the replacement of most major technological systems. Indeed, 50 years are enough time to turnover almost the entire capital stock of the society. About two-thirds of capital stock is usually in machines and equipment and about one-third in buildings and other structures. In Japan, the average renewal period for capital stock in business, the time it takes for machinery and equipment in an industry to be almost completely replaced, ranges from about 22 years in the textile industry down to ten years or less in such fast-moving industries as telecommunications and electrical machinery (see Table). In agriculture the estimated life span of cultivars in the United States is seven years for maize, eight for sorghum and cotton, and nine for wheat and soybeans13, and most experts believe the life span of cultivars will grow shorter, Relative to greenhouse warming, turnover is also fast for nonmachinery capital stock, which includes buildings, pipelines, and so forth. According to recent surveys in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1985 some 60 per cent of the stock is less than 20 years old and in the Soviet Union some 80 per cent is less than 20 years old (Fig. 2).

At first such figures may surprise us. But some reflection about the built environment relieves the surprise. Consider the office space in a modem city. Most of the space is in buildings completed in the last 20-30 years. These new buildings are filled with new equipment, for example, new telephone systems. Indeed, even older buildings are filled with modem equipment that did not exist 15 or 20 years ago. The same is true for super markets, restaurants and other stores. A large fraction of residential housing is similarly young and, in turn, filled largely with new domestic appliances of all kinds. If societies grow at a rate of 2-3 per cent per year, as the industrialized societies have for the past 150 years, then half of all capital stock will always be younger than 30 years old.

Probably the systems that take longest to build are infrastructures. Even these are constructed in less than a century14. Many infra structure systems are (or should be) continuously reconstructed. For example, roads are repaved every 5-15 years, depending on use. The 7,000-kilometre canal system of the United States was almost entirely built in the 30 years between 1820 and 1850. More than 90 per cent of the 300,000-mile US railway network was laid in the 65 years between 1855 and 1920. The paving of virtually the entire six million-kilometre surface road system of the United States was accomplished between 1920 and 1985. The US interstate highway system was completed in about 30 years from the time that it was announced by President Eisenhower. It is interesting to consider whether climatic change could re quire any public works on this scale; coastal protection and interbasin water transfer would seem the most likely candidates.

Because capital stock continuously turns over on a time scale of a few decades, it will be possible to put in place much technology that is adjusted to a changing climate. This ran be done without extraordinary measures given reasonably accurate information about the future. For the shortest lifetimes, even accurate information about the present climate will do.

That perhaps 90 per cent of the global capital stock in the year 2040 will be bat after 1990 does not diminish the significance of some long-lived structures. Action may be necessary to protect cities such as Venire, where preservation of historic buildings is the goal. In such cases, the process of replacement is not relevant.

The adaptations for long-term climatic change will probably mostly be the same as for other climate variation. The technologies, small and large, that buffer human activity over the long-term will be the same ones that mollify the difference between day time and nighttime temperatures, protect against normal variability between days, shield from storms and hail, adjust to the sea sons, and adapt to the wide range of climates where people already live.

No one has yet presented a radical innovation uniquely adaptive for the greenhouse effect. The main innovations directed at the greenhouse effect are so far organizational, in particular research groups in universities and government and assessment groups, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). If the future green house climate in any place will consist of climates that already exist somewhere on Earth, then many of the adaptations may look familiar.

Because the population of the world is imploding into cities, it seems logical that technologies that make cities habitable in un-welcoming climates will be among the technologies that are most important. Houston, Phoenix and Toronto may offer lessons. The trend in such places is toward ever larger en closures of space and passageways connecting them, where workers and shoppers are not subject to the elements. Already during much of the year in such cities few people are seen outside on the streets. Technologies for ‘smarter’ buildings and for more efficient building materials should be adaptive. Cities in developing countries, which are often in difficult climates to begin with and face worsening problems of urban pollution, may well lack the resources to apply such technologies to raise or maintain the quality of life in the face of changing climate.

Until this century much of the human struggle with climate was to keep warm. Because the struggle succeeded, in 1850 the population in Europe, a land of well chronicled and damaging winters, was three times as large as that of Africa and nine times as large as that of Latin America15. Now a main change in adaptation will be emphasis on technologies to stay cool. There is already pressure and success in this direction, population grows in tropical regions and people migrate south in temperate zones. Chemicals for refrigeration that do not exacerbate the greenhouse effect may thus earn a premium, and, of course, low greenhouse gas emission technologies to produce electricity and energy in general.

For water resources, larger-scale control of flows may be the trend. The Thames Barrage and the Netherlands Rhine Delta scheme may exemplify massive hydraulic systems that will be imitated in areas of major coastal populations. Freshwater systems in some regions would also be made more robust by extending networks of supply over wider spaces through interbasin transfer and other strategies. In practical terms, many of the technologies needed may be well-established, for example, tunnelling, pumps and other technologies traditional to civil and mechanical engineering, updated with electronic sensors and other devices for management and control. Technologies for management of water demand will be equally or more attractive in many regions; these would include not only hardware technologies for minimizing leaks, but also software technologies from operations research, as well as economic and other incentives.

In agriculture, with a few notable exceptions, most emerging technologies are expected to reduce substantially the land and water required16. At least in the United States the trends in agricultural technology are in the direction that should be sought in view of climatic change. Almost all technologies that are attractive for agriculture are only more attractive in light of the possibility of climatic change. Specifically, appealing directions for agricultural innovation might include diversification of crop production by varying maturity, heat and drought tolerance, input needs, and end uses; innovation in planting and spacing; collecting and recycling irrigation run-off; soil moisture conservation; better moisture-use efficiency and improved use of plastics and other new materials; resistance to pests and insects; management practices; institutional measures; programmes and facilities to support extreme contingencies; and infrastructure. Many of these are applications of information technologies, as well as biotechnologies and more traditional agricultural and mechanical technologies. It may be possible to design and select plants adapted to higher concentrations of CO2, and other changes in the atmosphere.

Though many innovations helpful in a rapidly changing climate are more likely to come from private enterprise than government, governments ran help in two ways.

One way governments ran aid adaptation is through timely information. One variety is assessments of the issues relating to climatic change. A second important and more operational variety of information is improved weather and climate forecasts. Eventually the climate of the far future will become to morrow’s weather. Information about it is likely to improve the possibility that it will be more resource than hazard.

There has been a gradual, measured improvement in weather forecasting during the past 20 years (ref. 17). In the greenhouse issue, all nations should find strong motivation to improve forecasts and the data and research underlying them. The quality of weather analyses and forecasts in many developing countries, especially in the tropics, is markedly lower than those in developed countries, particularly in the northern hemisphere. Advances in numerical modeling and extension of technology for monitoring in tropical regions can cause substantial improvements.

A third innovation in information relates to markets. The needs are for facilitation of information flows and improvements in rules for markets, in particular, markets for water. In many nations, water is allocated largely through administrative means based on water rights. Water transfers accommodate new patterns of climate, as well as changing farming and urban and industrial growth. They allow water to be used where it is most valuable18. Flexibility of water transfer is important, because the life of water projects is often 50-100 years or more19.

Substantial subsidies for water for irrigation, in particular, lead to prices that en courage inefficiency. ‘Mere is little incentive to conserve. Higher cost of constructing water projects and more demand and competition for water for such uses as preservation of wildlife, recreation, and cities make the issue serious. Several long-term con tracts in the Central Valley of California provide water for only $3.50 per acre-foot, whereas new sources of supply would cost the federal government or the state $200-300 per acre-foot per year for construction alone18. Allowing and encouraging voluntary marketing of the resource among users could help adapt to climate changes and produce economic benefits. Voluntary water transfers could take several forms, including permanent sales, long-term leases, short term leases, and leases contingent on drought.

Although markets may require innovation by government in providing information and rules, there are also traditional ‘hardware’ opportunities for innovation in public works. Government is the primary purchaser, financier and manager of systems of water supply and waste disposal, as well as coastal facilities. These take decades to site and construct and then can last generations. There may be opportunities for government to enhance innovation in infrastructure in light of the possibility of a changing environment.

Conclusion

Technologies are available for adaptation to climate on a spectrum of space, time and cost. Within minutes and for a few dollars one can buy an umbrella for local protection against a shower. Such technologies diffuse rapidly into the society, in a matter of months or years. Larger and more costly innovations, like electric refrigerators, may take 20 or 30 years to become pervasive. At the other end of the spectrum, large systems, like those for water and transportation take several decades or generations to extend themselves fully and may cost tens or hundreds of billions of dollars.

Technological performance has improved throughout human history, and in this century waves of innovation have come ever more rapidly20. In many systems, there have been steady improvements in efficiency of about two per cent per year, so that systems built today, for instance in energy, are about twice as efficient as those built 30 years ago21. Today generating a kilowatt of electricity in a steam plant takes only 15 per cent as much fossil fuel as at the turn of the century. A doubling of overall efficiency of several major systems should be possible just by replacing existing systems with best technologies and practices available today. This, of course, takes capital, and it is not clear that the expected rate of climatic change warrants an acceleration over the rate of change in physical capital stock that is already occurring, as long as the new stock is acquired with the best information about future climate in mind.

The general direction of change in technology and civilization is heartening for those anxious about climatic change. The trend is toward systems that are less vulnerable to climate. It would seem to be sensible to maintain this course and not to revert to reliance on such technologies as sailing ships and water mills that are more sensitive to climate. The highest need is probably to assure the inventive genius, economic power, and administrative competence that make the many technologies useful in adapting to climate available to the most people.

Figures

FIG. 1 Share of the workforce employed in agriculture21.

FIG. 2 Age distribution of nonmachinery capital stock in the FRG, data for 1985 (ref. 23) (hatched bars), and in the Soviet Union (solid bars), data as of 1986 (USSR State Committee on Statistics, Statistics on social indicators and capital vintage structure in industry, undated memo, Institute for Social and Economic Statistics, Moscow; courtesy of A. Grübler, Laxenburg, Austria).

Table

CAPITAL STOCK RENEWAL

| Industry | Renewal period |

|---|---|

| All Industries | 13.4 |

| Manufacturing (all) | 15.8 |

| Electrical machinery | 9.8 |

| Transport machinery | 13.2 |

| Pulp and paper | 13.7 |

| General machinery | 14.2 |

| Food stuff | 16.7 |

| Steel and non-ferrous metals | 21.1 |

| Textiles | 22.5 |

| Non-manufacturing (all) | 11.8 |

| Service | 8.1 |

| Transport and Telecommunications | 10.7 |

| Construction | 11.9 |

| Finance and insurance | 12.8 |

| Distribution | 15.6 |

| Real estate | 15.8 |

| Electricity, gas and water supply | 15.8 |

CAPITAL STOCK RENEWAL: Average renewal period for capital stock of business corporations in Japan by industrial sector, 1986-87 (ref. 22).

References

1. Nordhaus, W. D. Setting National Priorities. Policy for the Nineties (ed. Aaron, H.) 185-211 (Brookings, Washington, 1990).

2. Adams, R. McC. & Nissen, H. The Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1972).

3. Newman, L. F. (ed.) Hunger in History: Food Shortage, Poverty, and Deprivation (Blackwell, Oxford, 1990).

4. Desmond, K. Harwin Chronology of Inventions, Innovations, and Discoveries from Pre-History to the Present Day (Constable, London, 1986).

5. Schelling, T. C. in Changing Climate (National Research Council) 449-482 (National Academy Press, Washington, 1983).

6. Escudero, J. C. Climate Impact Assessment (eds Kates, R. W., Ausubel, J. H. & Berberian M.) 251-272 (Wiley, Chichester, 1985).

7. Weihe, W. H. Proceedings of the World Climate Conference 313-368 (World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, 1979).

8. New York Times, 1 August 1990, p. C1.

9. Warrick, R. A. Climatic Constraints and Human Activities (eds Ausubel, J. & Biswas, A. K.) 93-123 (Pergamon, Oxford, 1980).

10. Reynolds, T. S. Sci. Am. 251(1) 122-130 (1984).

11. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Scientific Assessment of Climate Change, Report to IPCC from Working Group 1 (World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, 1990).

12. US Bureau of the Census Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1990

110th edition (US Government Printing Office, Washington, 1990).

13. Duvick, D. N. Econ. Botan. 38, 161-178 (1984).

14. Grübler, A. The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures: Dynamics of Evolution and Technological Change in Transport (Physica, Heidelberg, 1990).

15. McEvedy, C. & Jones, R. Atlas of World Population History (Penguin, New York, 1978).

16. Office of Technology Assessment, Technology, Public Policy, and the Changing Structure of American Agriculture (US Government Printing Office, Washington, 1986).

17. World Meteorological Organization (WMO) The World Weather Watch: 25th Anniversary 1963-1988 (WMO No. 709, Geneva, 1988).

18. Wahl, R. W. Markets for Federal Water: Subsidies, Property Rights, and the Bureau of Reclamation (Resources for the Future, Washington, 1989).

19. Waggoner, P. E. (ed.) Climatic Change and US Water Resources (Wiley, New York, 1989).

20. Mensch, G. Stalemate in Technology (Ballinger, Cambridge, 1979).

21. Nakicenovic, N. & Grübler, A., Technological Progress, Structural Change and Efficient Energy Use: Trends worldwide and in Austria, International Part (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, 1989).

22. Economic Planning Agency Economic Survey of Japan, 1987-1988 (Tokyo, 1989).

23. Statistiches Bundesamt Wirtschaft und Statistik 4/89 (Metzler-Poeschl, Stuttgart, 1989).

Where is Energy Going?

This article appeared in the magazine The Industrial Physicist, published by the American Institute of Physics, in the February 2000 issue.

The essay had appeared in Italian in the special millennial edition of the Italian financial newspaper, Il Sole/24 Ore, on 17 November 1999; also in Italian as Benvenuti nel millennio nucleare, pp.163-168 in Duemila: Verso una societa aperta, M. Moussanet, ed., Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano, 2000.

There was an error in the printed version of Figure 3. Both the figure labeling and caption are wrong. The error has been corrected in the PDF version here and on The Industrial Physicist web site.

Figure 3 should read:

Figure 3. When total world per capita energy consumption (tons coal equivalent) is dissected into a succession of logistic curves, normalized on a scale that renders each S-shaped logistic pulse into a straight line, energy history is a succession of growth pulses evolving around the lead energy commodity of the era. In each era, consumption triples. “F” is the fraction of market share.

To view a PDF on your computer, you can download Adobe Acrobat Reader from Adobe at https://www.adobe.com/.